When developing green spaces, the most important considerations usually revolve around convenience (which species requires the least maintenance?) and aesthetics (which would look the most beautiful?) and quantity (What is the area of green space per capita in a city?). In this post, I argue that much more value can be derived by adopting a 3-step framework that designs a well-rounded urban forest with a purpose in mind.

- What is a well-rounded urban forest?

- What are the shortcomings of conventional urban forestry?

- Planning and designing urban forests with a purpose

Planning urban forests with a purpose is all about maximizing ecosystem services.

What is a well-rounded urban forest?

When planning an urban forest, 4 important questions need to be addressed (Govindarajulu, 2014):

- Quantity: what percentage of the urban area is filled with green space?

- Quality: can the green space improve urban biodiversity and provide better ecosystem services?

- Connectivity: how much of the green space is connected?

- Accessibility: how much of the population has access to the green space?

In addition to these 4 parameters, this post includes a purpose to design, specifically targeted at deriving one or more ecosystem services from urban forests (while also influencing the other 4 parameters).

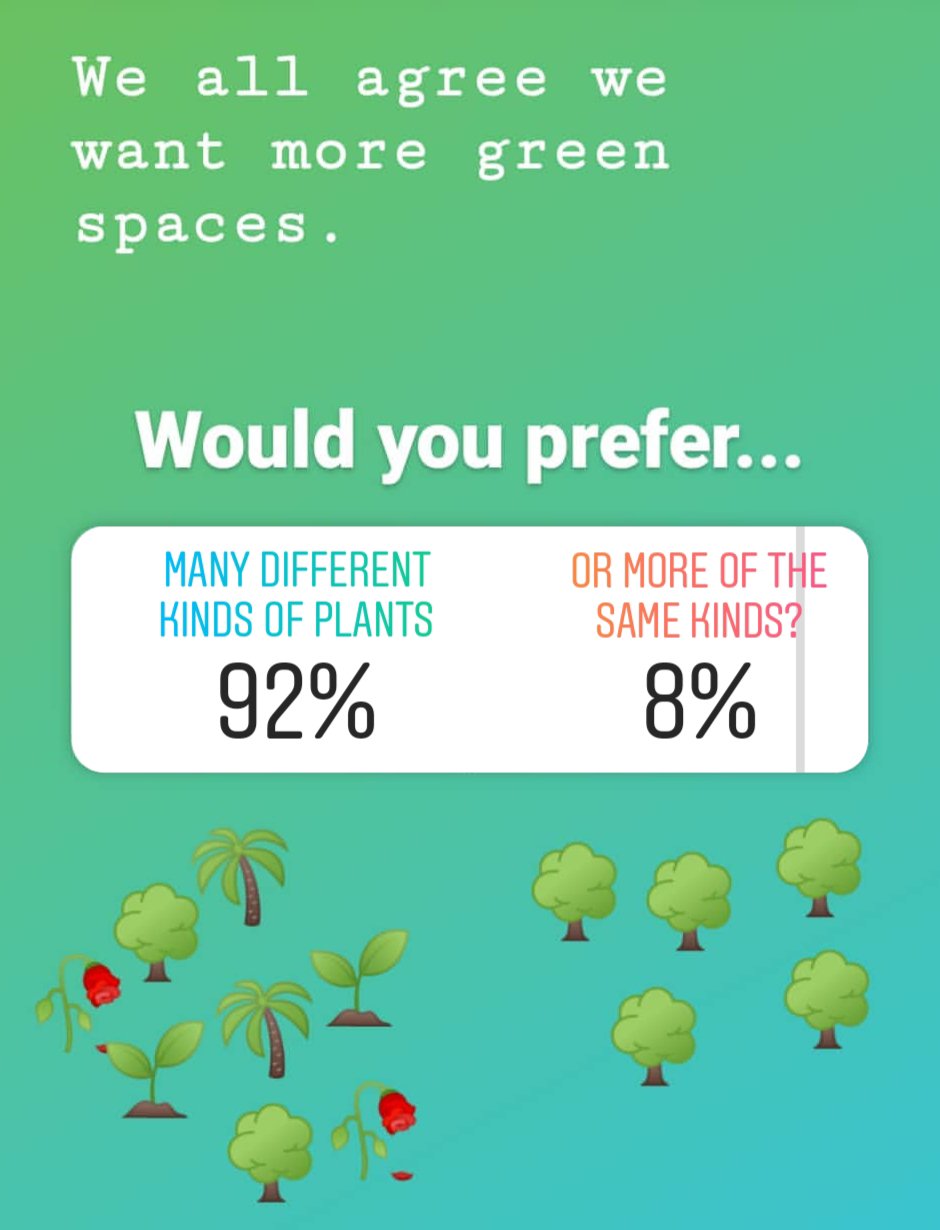

Such a urban forest would have diverse (predominantly) native species with temporal and spatial spread to meet one or more specific purposes, including but not limited to aesthetics.

Conventional urban forestry plans, however, concentrate on quantity and (in some cases) accessibility parameters alone. Diversity, connectivity and purpose parameters are found missing.

What are the shortcomings of the conventional approach?

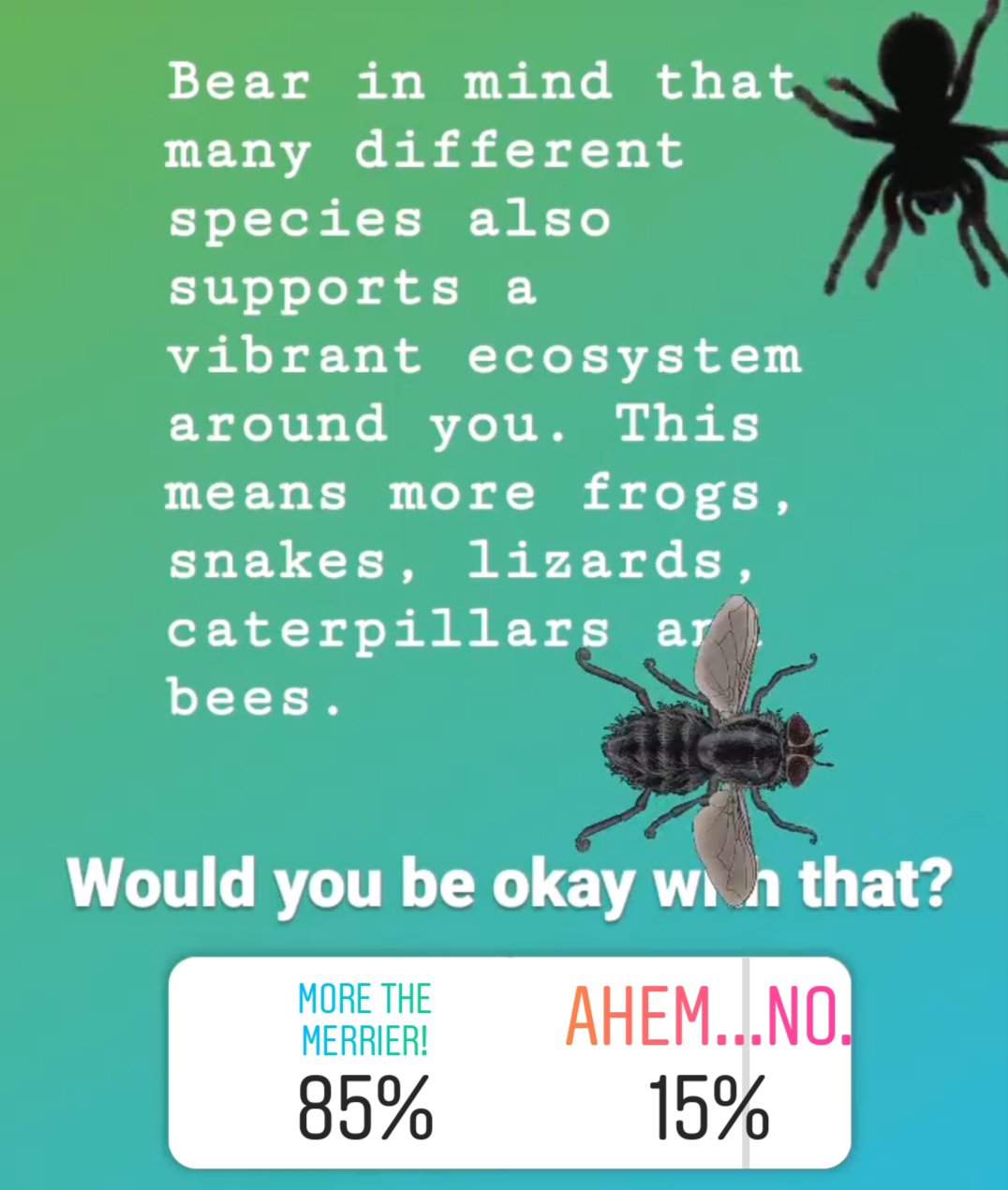

Conventional urban forestry seeks to establish the forest or green space quickly and look beautiful. Urban forest ecology and succession is rarely given importance, evidenced by the minuscule number of experimental research on urban forest succession lasting greater than 5 years (Oldfield, et. al. 2013). Urban biodiversity also remains relatively unexplored (Singh & Bagchi, 2013). We forget that forests are complex ecosystems, supporting a wide variety of processes and organisms. Urban forests are no different.

Such an approach has many issues. First, to ensure fast growth and aesthetic appeal, a small number of (often) inappropriate non-native species may be planted. Planting the same kind of trees and plants may make it easier to maintain, but drastically reduces the resilience of the urban forest towards diseases, pests and climate variation. One disease outbreak can wipe out the entire forest! These forests require greater care to ensure survival.

Second, ecological processes are overlooked. Even trees planted along tree dividers form an ecosystem, with the associated bushes, soil mircofauna and urban wildlife like squirrels and birds. A new species of flora or poor species diversity in these ecosystems could affect its stability.

Third, introducing non-native species leaves the urban ecosystem vulnerable to invasive species. Either the non-native species itself is invasive (thus spreading fast and disturbing the entire urban ecology, as in the case of the infamous Lantana camara), or it may develop into a poorly established urban ecosystem that has many open niches for invasive species to colonize.

Fourth, non-native and aesthetically appealing species may not serve the other utilities derived by citizens. This could breed resentment towards the forests, considering them a “waste of precious land”.

Finally, a quantitative focus to improve green cover alone does not guarantee the desired ecosystem services. Though the tree cover in Delhi increased from 6.61% in 2003 to 8.29% to 2009, the city witnessed a considerable rise in urban temperatures during the same period.

Planning and designing urban forests with a purpose

An urban forest plan with a purpose is all about maximizing the ecosystem services derived from them. This purpose-driven framework encompasses all of the parameters which comprise a well-rounded urban forest.

With this in mind, let us look at the 3 steps we can take to plan an urban forest:

Step 1: Knowing what to plant

The first step is to identify an appropriate list of species. Tree census is a wonderful way to understand the kind of trees that can grow in a particular environment. After the Ministry for Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) announced a national tree census in 2015, tree census has been undertaken in various cities, for example in Bengaluru. Similar initiatives have been undertaken by independent conservation organizations like the “Delhi Landmark Tree Map” by Vertiver and IORA Ecological Solutions for New Delhi. The iTree initiative is an example where citizens conduct the inventory of urban trees. Local participation by enlisting residents, schools and colleges in this step is strong way to gain the support of the final benefactors of the urban forest.

While the onus is on planting native tree species that can support naturally evolved ecosystems, climate variability and human impacts on the environment has stressed urban ecosystems to a point where some native species are now unsuitable. In such cases, use of non-native species in planning the urban forest can also be considered provided they are not invasive. They can be more resistant to pathogens, and provide better ecosystem services.

Step 2: Understanding the local ecology

Most cities have some urban forests historically embedded in them due to religious, aesthetic or economic purposes. These are areas of thriving biodiversity, and can be a lens to view the natural ecosystems of an urban space. Home gardens, for example, can house a variety of insect and reptilian species, as vividly described by Harini Nagendra in her book “Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present and Future“.

This step can be useful while planning an urban forest for a variety of reasons.

- It identifies the invasive species that have crept into the existing ecosystems. This could help us manage urban forests better, promoting on site diversity by keeping competitive exotics from out-competing native herbaceous species (Rebele & Lehmann 2002).

- It helps us understand which species are useful for local communities; Bengaluru urban villages and slums have a preference for drumstick and neem trees for the variety of utilities they offer to the local communities. These species can be preferably selected for designing an urban forest, and placed in accessible locations for the community.

- Knowing existing species composition can inform decisions related to habitat requirements of the biodiversity, and consequently, the connectivity of the urban forest.

- Designing urban forests suited to local conditions ensure better survival; in case the future sees mismanagement or neglect of the urban forest, we will not face a situation where the species composition becomes undesirable due to natural ecological succession. Rebele & Lehmann (2002) noted that on a capped landfill in Berlin, Germany unmowed plots had 80% vegetation cover in the fifth (and final) year of the study, but two invasive species comprised 45% of the cover.

Step 3: “Enabling” indicators to drive design

Enabling indicators influence design decisions as well as monitor results, as against performance indicators which simply monitor results (Barron, Sheppard & Condon, 2016). Identifying enabling indicators depending on the purpose(s) is a new approach to planning urban forests. For example, “tree canopy cover” is a commonly used enabling indicator addressing quantitative aspects of an urban forest, as against “per capita area of green space” which is a performance indicator.

Urban forests provide stormwater management, carbon sequestration, disaster resilience and air quality improvement, among other ecosystem services. Visual and physical access to nature are important psychological benefits, according to studies (Kalpan, 2001; Hartig, et. al., 2014). Using enabling indicators in an urban forest plan will ensure that these ecosystem services are truly derived.

“Urban tree diversity” and “physical access to nature” are considered two of the most common indicators for urban forests that can influence the number species chosen, ages of trees and, spread of the urban forest in the city. Other popular enabling indicators for urban forests are canopy cover, stormwater control and air quality improvement. A more specific purpose, say a mangrove urban forest for coastal resilience, could have sub-indicators like “width of the buffer” and “root density of the trees” driving the design.

Enabling indicators for planning urban forests can be developed to capture the spatial extent (quantity, accessibility, connectivity), diversity (quality), and ecosystem services (purpose), covering all 5 parameters of a well-rounded urban forest.

Forest certification is an example of a tool to direct such an “indicator-driven” urban forest design. A unique urban forest certification scheme could incorporate this framework to plan the urban forest. A certification procedure also has other advantages like creating accountable management and providing access to markets for timber and non-timber forest produce harvested from urban forests. One example of an urban forest certification scheme is the Trees-outside-Forest (ToF) certification scheme developed by the Network For Certification and Conservation of Forests (NCCF) in India.

The 3rd step is an opportunity to bring multi-disciplinary coordination between architects, landscape specialists, designers, private sector as well as government stakeholders in financing and designing the urban forest.

In conclusion…

Today, deteriorating environment quality and climate disturbances in urban spaces have spurred innovative action and renewed importance of urban green spaces. I strongly believe that a planning and designing urban forests with a purpose-driven framework is a powerful method to improve the urban environment quality and resilience in a tangible way.

Interesting piece. It does take local participation to secure a successful urban reforestation project. They are the benefactors (along with the wildlife that will move in) so it is important to get an enthusiastic cooperation and help with fundraising.

I would also think about both using the Ecosia Browser (it plants trees with profits) and contacting them to see if they can help to fund such a project.

Good luck. It is a great plan. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, thank you for reading!

Absolutely, it is important to undertake local participation and consider their preferences. I’ve captured this under the “tree census” part of the plan. Likewise, the social interactions with ecology highlights the need to plant species that residents find use for.

I have heard of the Ecosia browser, and it is truly a great initiative. I’ve heard they are undertaking massive reforestation measures after the Amazon fire. I wonder if they’ll be willing to support financing urban forests as well.

LikeLiked by 2 people

One of the newest thoughts to planting urban forests, is to intermix fruit and nut bearing trees that the locals can harvest to sell in markets. Some very degraded crop lands (Rice, Wheat, cotton) where drought has affected the productivity of the soil, are being implemented to help the local economy. 😊 I hope Ecosia will help.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, in fact I covered this option of planting fruit bearing trees as a way to finance urban forests as well as support livelihoods in an earlier post: https://eco-intelligent.com/2019/08/27/5-promising-financing-options-for-urban-forestry-in-india/

I’ve heard that the LDN Fund under UNCCD is also looking for such opportunities (they are looking for this in agroforestry, apparently).

LikeLiked by 1 person

We do need to get planting don’t we. I agree with all your points on proper planning though. I expect you know about the high rise ‘forests’ of Milan, Bosco verticale https://www.stefanoboeriarchitetti.net/en/project/vertical-forest/

LikeLiked by 2 people

We really do, and we need to do it properly!

I have read about the Milan vertical forest, yes. It is one of the prime examples of urban forestry in the world! (this website you have linked is a fascinating resource. I have bookmarked it, thank you.)

LikeLiked by 2 people

You might be interested too in this New Zealand example of reforestation

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll check it out, thanks Tish!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Tish, just watched this (it would be called a documentary, right?). A beautiful and inspiring story indeed. And a for it to have been an individual effort!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it’s a great documentary. Just shows what can be done, and how natural systems will reassert themselves given half a chance. The notion of simply letting a rabid pest invader plant do its stuff until it is naturally overwhelmed and dies, is pretty astonishing.

LikeLike

True! I suppose “time” is the biggest factor here. With enough time, natural ecological succession will take over and establish the appropriate climax community for that ecosystem no matter what changes we had made.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] forestry planning and financing for ecosystem services have been extensively discussed here and here on Eco-intelligent. The money invested in expensive construction and reconstruction […]

LikeLike

This is true, especially with invasive species. In Washington where I live, scotch broom has taken over a lot of spaces and it’s impossible to remove it all. It’s really important to think about what a potential plant can do to an environment.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Agreed. This is a problem faced by almost every city in the world.

Thank you for commenting!

LikeLike

Have there been initiatives taken by the local government to get rid of the scotch broom?

LikeLike