Article summary:

The article highlights important climate terms used in today’s discourse. Each term is described with an explanation, followed by links to resources to follow-up on the latest developments. Some additional, linked terms are also described within each section (for example, carbon credits under carbon markets).

If you are already familiar with these terms, I encourage you to dive into the resources and links. I’ve found some really interesting websites and articles during my research. Use the links below to navigate through the article.

The climate crisis continues to worsen with more frequent and more intense disasters. Governments, companies, media, and people are frantic. New decisions, announcements, and updates arrive everyday. Here is a short glossary of the most important terms you should know to navigate this space and stay well-informed.

Adaptation

The two fundamental concepts of climate action remain highly relevant in the climate discourse of 2025.

Climate change adaptation now dominates international climate politics because the effects of climate change are already here and we need to deal with them. How do we deal with these effects — floods, erratic rainfall, droughts, extremely intense storms, seasonal variations?

What does it mean?

Climate change adaptation covers any activity that helps us adjust to already occurring impacts of climate change. This could include:

- Planning and preparing disaster response teams for flash floods in hilly terrain.

- Changing cropping patterns to account for varying rainfall.

- Storing more food to prepare for droughts.

- Moving from coastal areas that are experiencing sea-level rise and increasing groundwater salinity to inland areas.

The upcoming Conference of Parties (CoP) under the United Nations Convention for Combating Climate Change (UNFCCC) is expected to discuss adaptation extensively.

Hot topics of discussion

- Global goal on adaptation under the UNFCCC. Read more here.

- Creating country-level National Adaptation Plans (NAPs). Read more here for the process under UNFCCC. Check out this link for the developments in NAPs supported by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Related terms

Climate change mitigation

If adaptation is one side of climate action, mitigation is the other.

What does it mean?

Climate change mitigation covers any activity that stops climate change from getting worse. Since climate change is primarily driven by greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from human activity, mitigation includes any action that reduce or stop GHG emissions. Here are a few examples:

- Adopting renewable energy sources like solar and wind over fossil fuels based energy sources like coal or natural gas

- Reducing flight travel

- Improving energy efficiency in building lighting

- Changing steel/cement making processes or equipment to to those that release fewer carbon dioxide

Here’s a fun schema to quickly identify if an activity helps mitigate climate change, or helps adapt to its impacts. Suppose a child has poor eyesight. Performing regular eye exercises keeps her eyesight from getting worse (mitigation). But she already has poor eyesight – how is she to deal with that and live her life? She adjusts to this new reality by wearing spectacles (adaptation).

Mitigation has so far been given more attention in climate discourse because it is relatively simple to grasp and implement. Technological solutions exist around which business models can be created, thus building on existing economic models. Momentum on mitigation continues but the onus is slowly shifting to private enterprise action, as opposed to adaptation that continues to rely heavily on government action.

Hot topics of discussion

- Technological advances in carbon capture and storage.

- Forest management to improve carbon sequestration. Read more on the latest tracking here.

- Reducing emissions from industry through market approaches (see carbon markets below) and carbon pricing.

Related terms

Net-Zero

Every major country and company has announced a “net-zero” target. From 2025 onward, the discussion will progress to how net-zero can be achieved.

What does it mean?

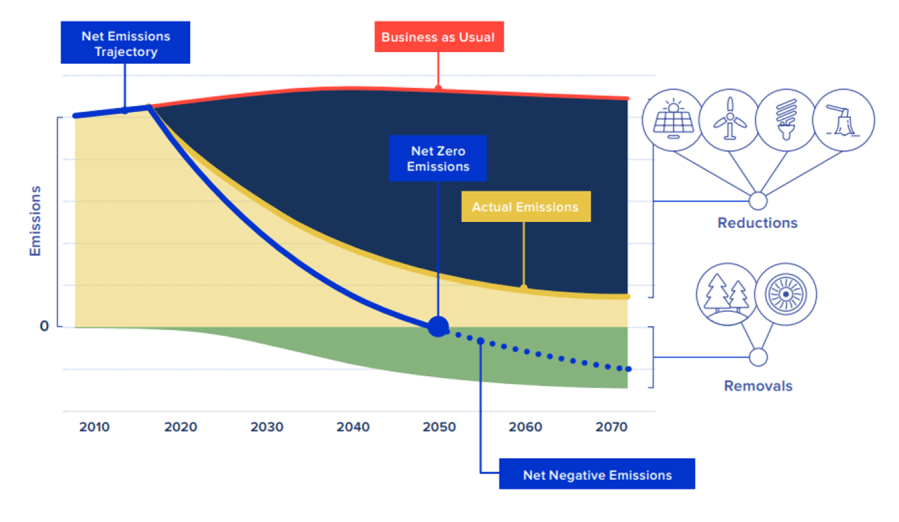

Net-zero is a state when an entity effectively has no emissions, thus not contributing to climate change. This is achieved in one of two ways: 1) when the emissions are reduced to zero; or 2) are reduced as much as they can be and the remaining emissions are compensated for by pulling an equal amount out of the atmosphere (through technologies like carbon capture or by planting trees).

Net-zero is often defined with a target year. From today till that target year, the entity follows a “net-zero trajectory” which describes how emissions will be reduced incrementally, and how residual emissions will be compensated for.

Achieving net-zero through the first condition is simple; just switch to zero emissions practices and technologies. Achieving net-zero through the second condition is tricky. If you see an organization claiming to be net-zero by simply compensating for all of their emissions, this is a false claim and can count as greenwashing. The concept of net-zero stresses that an entity must first reduce their emissions as much as possible. Only then can it compensate them remaining emissions through tree-planting or carbon credits.

Company X emits 100 tonnes of GHG emissions in a year and has decided to achieve net-zero by 2028.

Option 1: A cunning employee realizes that 100 tonnes is not a lot. The company can simply buy 100 carbon credits (see below) and compensate for all its emissions! Company A can be net-zero tomorrow!

Option 2: The company’s Sustainability Division examines its operations. It realizes that 40 tonnes of annual emissions can be reduced by switching to a new machine available in the market. A further 20 tonnes can be reduced by streamlining a process that is currently spread across a wide geography. The Division makes these recommendations to its Board, which are taken up seriously. These account for 60 tonnes of the annual emissions. The remaining 40 tonnes are compensated for by purchasing carbon credits from the carbon market (see below).

Which of the two options is the acceptable path to net-zero?

Hot topics of discussion

- Track net-zero commitments of companies and countries here.

- Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) – the private sector’s most recognized guide to charting net-zero pathways that are in-line with the Paris Agreement goals.

- Banks that were a part of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA) are quitting the group. Read more here, here, and here.

- The international shipping industry has adopted a net-zero pathway. Read more here.

Carbon Market

The market-oriented description of the climate crisis says that carbon (and GHGs) is an “externality”, a by-product of today’s industrial and economic processes that is not factored into the costs of a company. So, GHGs have been released into the atmosphere with abandon. If we have to address this problem, we can simply put a price on these emissions. If companies see it as a cost, market forces will demand that they reduce this cost by reducing their emissions.

How can we price emissions and create an incentive for companies to account for their emissions as a cost? We can tax carbon emissions, or we allow the hand of the market to guide us.

What does it mean?

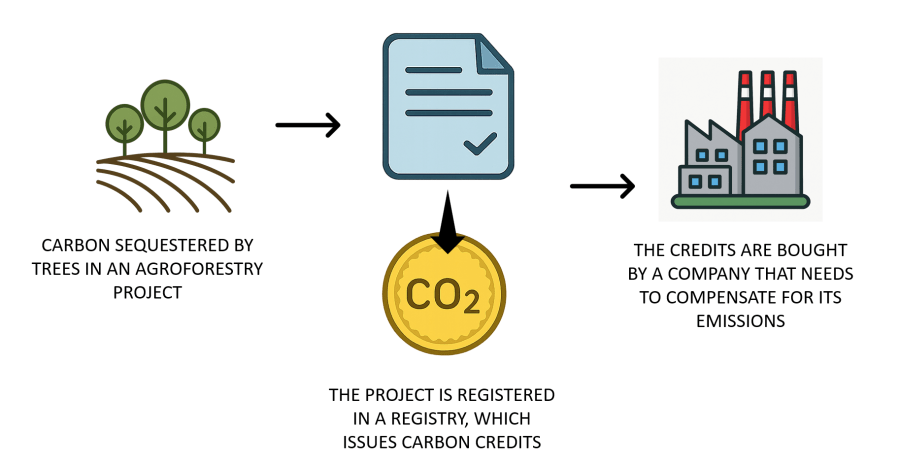

The market system begins with targets. Companies are mandated to reduce their emissions below a certain level by the governments. The companies that reduce more emissions than they are mandated to (i.e over-performers) get “carbon credits”. A carbon credit is equal to 1 tonne of emissions reduced/removed. The companies that cannot meet their targets (under-performers) either have to pay a fine, or they can buy carbon credits from their over-performing peers. Supply and demand will set the price of these credits. This should ideally be less than the fine, thus incentivizing under-performers to buy credits. Over time, the targets become more stringent. Companies must reduce their emissions more and more by either buying more credits or innovating low-emissions processes for their business.

The voluntary carbon market

Not all companies receive targets. Governments can choose to gradually introduce new sectors into their market system over several years. For the companies that do not receive targets but still want to reduce emissions (to maintain a brand, build a good PR or simply prepare for future targets), they can buy carbon credits from entities outside of the market system. This is called the voluntary carbon market since both the companies buying carbon credits and the entities producing these credits act voluntarily. Who ensures that these credits are truly based on reduced emissions and trustworthy? Independent standards verify these credits, building the trust required for this market to function.

A related-term that you will often hear is a carbon offset. A carbon offset is equivalent to a carbon credit — both account for 1 tonne of emissions reduced/removed. While a carbon credit is the official term used in government-mandated carbon market structure, a carbon offset is an emission reduction either bought from the voluntary carbon market or outside of your company’s operations and jurisdiction.

Hot topics of discussion

- Find the latest market updates on Ecosystem Marketplace (free resource) and carbon pulse (paid resource).

- Article 6 of the Paris Agreement is about a United Nations-governed carbon market. Learn more about it here.

- India will soon launch a carbon market system. Here’s how it might look like.

- The Carbon Pricing Dashboard is a fantastic resource that tracks all carbon markets and carbon pricing systems around the world.

Climate Finance

Climate finance seems simple at first, but closer scrutiny reveals many conditions and complications. No wonder it is one of the most controversial and debated topics in international climate negotiations.

What does it mean?

Climate finance is any money committed and used for adaptation and/or mitigation. More recently, it also includes money committed to loss and damage.

Climate finance is an important topic in the international climate discourse. Under the UNFCCC processes, historically large emitters (developed countries) have committed to providing climate finance to emerging economies and least developed countries. The years of negotiations concern, a) how much finance the developed countries should provide, commensurate to their historical responsibilities and the true needs of the developing countries suffering from climate impacts; b) in what form does this finance flow (primarily through grants and loans — developed countries want to include loans as a significant instrument which developing countries find unacceptable); and c) who provides these loans (is it the country governments from their public finances, or should private capital count towards such commitments).

The latest CoP of the UNFCCC in Baku came out with a New Collective Quantified Goal, where developed countries will mobilize at least $300 billion annually for developing countries by 2035.

Climate finance is not to be confused with green finance. Green finance is any finance committed to environment-friendly activities. This can include plastic recycling, sustainable waste management, water purification projects, etc. However, these activities don’t count as climate-friendly activities; financing for these activities will not be a part of climate finance. Climate finance is a sub-set of green finance.

Hot topics of discussion

- Green taxonomies are being developed by country governments to channel private investments into critically important sectors and prevent greenwashing. Read more here.

- The latest updates on UNFCCC negotiations concerning climate finance here.

- Climate Policy Initiative’s Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2025 Report.

- There has been a constant call for ‘innovation’ in climate finance. This is to overcome barriers in traditional financial systems that are not conducive to climate-focused initiatives. Read about some of these initiatives here and here.

Nature-based Solutions (NbS)

What does it mean?

Any action that uses natural processes or nature’s structures to address our environmental and social problems are NbS. While this can also include solar energy and wind energy (because we are using nature to produce energy), the term usually covers those activities that involve ecosystems and their sustainable management/recovery. Typical examples of NbS include:

- Reducing landslide risks with urban forests and trees on slopes.

- Using urban greens to reduce urban flooding.

- Managing grasslands for climate change and livelihood protection.

- Protecting coral reefs and planting mangroves to reduce the risk to coastal infrastructure during storm surges along with a whole host of other case studies.

NbS is the other side of the coin symbolizing solutions to the climate crisis and environmental degradation — the technological solutions called geo-engineering . The advantage of NbS is that they provide several co-benefits to a wide range of stakeholders apart from addressing the core problem they are deployed for.

A common comparison between NbS and geo-engineering is planting trees versus carbon capture and storage (CCS) to pull out carbon from the atmosphere. While planting or restoring a local forest can take time, the benefits are manifold — not only do the trees pull carbon out of the air but they also provide shade, fruits, a place for children to play and the elderly to lounge, birds to nest and squirrels to scamper. On the other hand, CCS can be faster and takes much less space. An entity can usually take the sole decision of installing CCS units near their operations and address their carbon footprint.

Which is better? That depends on who you are and what you want to achieve.

Hot topics of discussion

- The current decade is termed the UN Decade for Ecosystem Restoration, signifying the importance of ecosystems and nature in our lives and stresses on adopting NBS for our challenges.

- An IUCN discussion paper summarising the latest on NbS (until 2024).

- Linking NbS with net-zero goals.

- Mongabay is one of my favorite resources for environmental news, and their series on NbS is an extensive, fascinating read.

You might have noticed that a lot of these terms lead to one another. There is also much nuance within these terms (for example, carbon credits versus offsets or green finance versus climate finance). Understanding them will not only help you navigate the global discourse better but will also help distinguish greenwashing. Your awareness and ability to detect untrue claims is extremely important in today’s world misinformation. Stay sharp!

Have I missed any term? Let me know in the comments and I will be sure to include them.

Discover more from Eco-intelligent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.